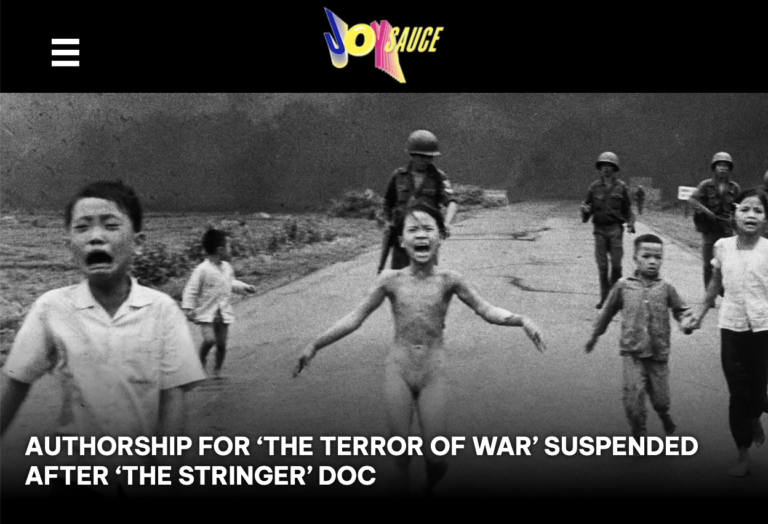

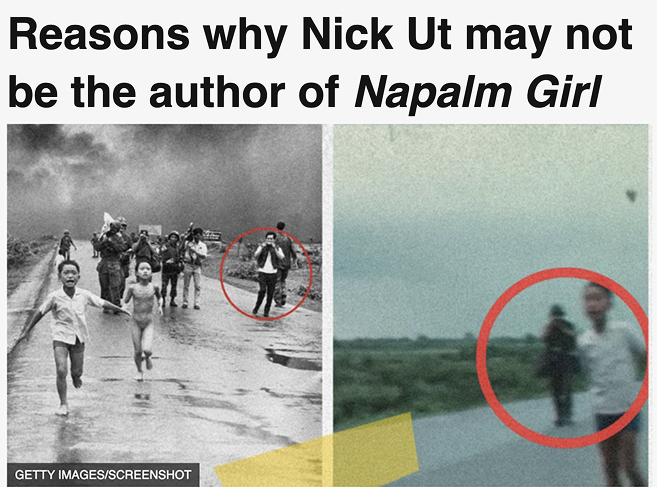

On May 16, World Press Photo, one of the most respected institutions in photojournalism, made an extraordinary decision: it suspended the attribution of the iconic “Napalm Girl” photograph. This action follows an independent investigation conducted by forensic analysts and media experts. Their findings conclude that, based on the available visual and technical evidence, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, a long-overlooked Vietnamese stringer, appears more likely than Nick Út to have taken the photo.

This renewed examination was prompted, in part, by the evidence presented in THE STRINGER, an investigative documentary I directed in close collaboration with a team of journalists and film crew, many of whom are Vietnamese. This recognition is deeply meaningful to all of us involved. But above all, it represents a critical first step in acknowledging the man we believe is the rightful photographer: Nguyễn Thành Nghệ. We hope the world will come to know and say his name.

THE STRINGER is not a film about Nick Út or the Associated Press. It is a story about truth, memory, and the quiet burden of a man who carried a secret for over fifty years, and the family who carried it with him. While one man was celebrated globally for a photograph that shaped the world’s understanding of the Vietnam War, another lived in silence.

Since our Sundance premiere in 2025, the film has sparked international conversation and inquiry. While we welcome open debate, the facts we present stand on firm ground, supported by testimony, documentation, and now by the findings of an independent third-party review.

The turning point in this story began with Carl Robinson, a former AP photo editor, who made the decision in 1972 to credit the photograph to Nick Út. As he shares in our film, he knew at the time that it may not have been accurate, and he has been haunted by that choice ever since. His desire to set the record straight became the catalyst for a long-overdue reexamination of the image’s provenance.

This film is also about power – who gets to be seen, who is believed, and who gets to write history. Nghệ was a trained military photographer with years of experience, including time in Washington, D.C. But as a “stringer,” he lacked the institutional support and protection afforded to foreign press agencies. That disparity shaped not only his fate, but the historical record itself.

I’ve long carried the legacy of the war in fragments, through the silence of my parents, who lived near the 17th parallel during the war, and through the images of conflict that played endlessly on our television and in cinema, projected onto the walls of our memory whether we invited them or not. But alongside the sorrow was something else, something rarely acknowledged: the capacity of Vietnamese people not only to endure, but to speak. To witness. To create the very images that have shaped how history is remembered. Yet even when people like my parents and my community were central to the story, we were often invisible. As a Vietnamese American filmmaker, I grew up watching the war play out through narratives created by others. The failure to center Vietnamese voices, then and now, is part of the very silence this film hopes to challenge.

It is notable that the Associated Press did not interview Trần Văn Thân, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ’s brother-in-law and an NBC soundman who was on the scene. This omission, like others, reflects a broader pattern — one in which the voices of Vietnamese people have often been excluded from telling their own stories.

From the start, our intention was simple: to share the perspectives of Nghệ, his daughter Jannie, and his brother-in-law Thân — three people who held onto a piece of history with quiet resilience. To hear them now, and to share their story with care, is the heart of what THE STRINGER set out to do.

The emotional truths in this story — the grief of a man whose work was never recognized, the regret of another who wishes he had spoken up sooner — are impossible to ignore. THE STRINGER does not rewrite history. It fills in what was left out.

The announcement by World Press Photo signals a turning point. It affirms the need to look again at the stories we thought we knew. And it marks a step toward giving Nguyễn Thành Nghệ the recognition he has long deserved.

As Trần Văn Thân says in the film: “There is nothing more important than the truth. When the truth is disregarded, that’s when society becomes corrupted.”

Bao Nguyen,

Director, THE STRINGER