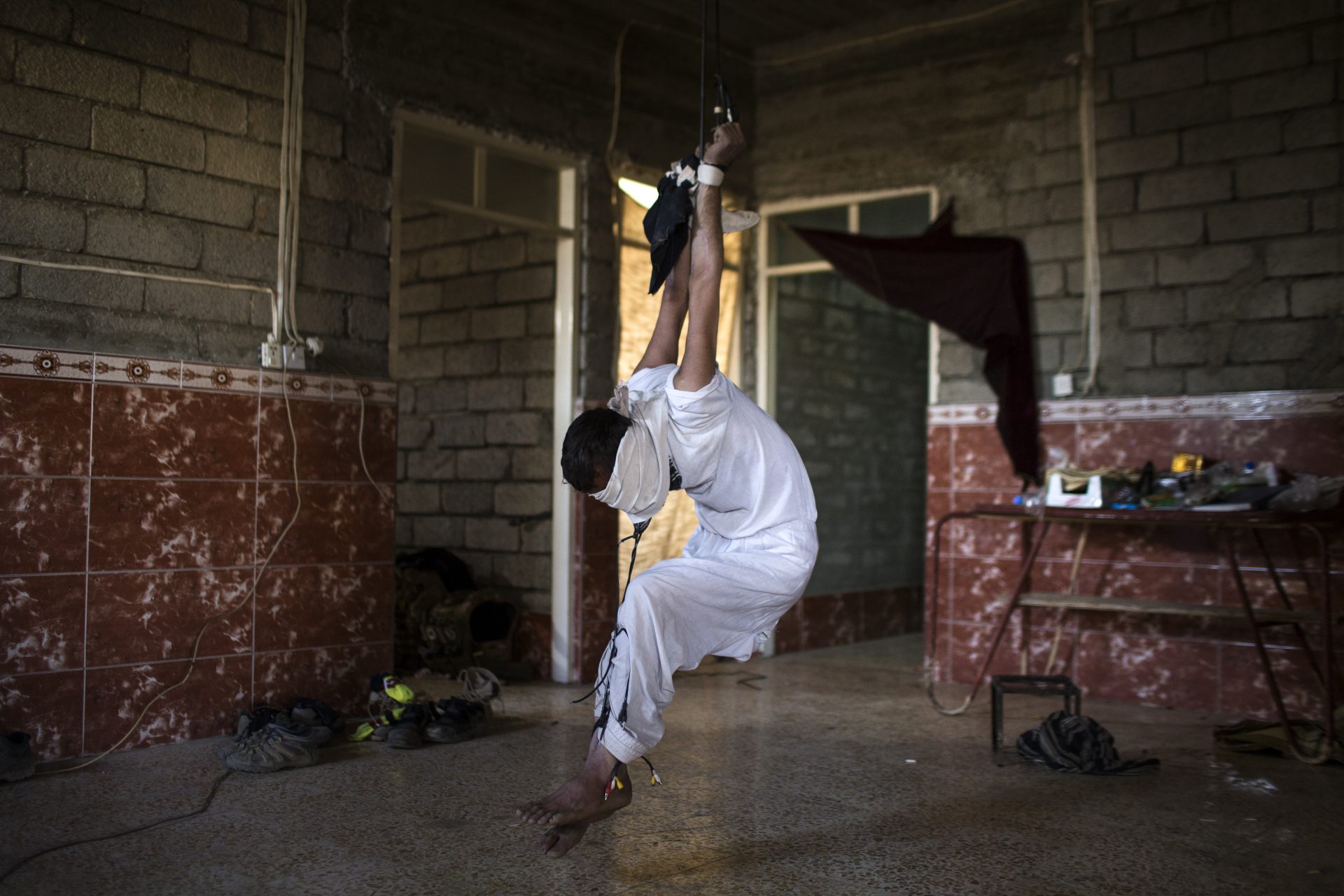

In the background of the photo, there’s a French-style white vanity mirror with wings. Reflected in the mirror is a bed with covers the color of fallen rose petals. Maybe it was bought for a bride or a newly married couple decorating their first bedroom in Mosul, Iraq, in the years before the ISIS war. It makes me think of new love and stability and fantasies of sepia-tinted beauty. There’s a framed certificate on the wall that’s too small to read. The light coming through the net curtains is golden, and there’s a red kerosene lantern on the vanity table. The only other splash of red in the room is the handkerchief used to tie up the blindfolded man dangling by his wrists from the ceiling.

The man is being jerked, strappado style, on chains hanging down from between the knots in the red handkerchief. A soldier in camouflage fatigues stands in front of the hanging man with one hand on his hip. His baseball cap is worn backward, and he is giving a thumbs-up sign to the photographer. There’s discord and terror in the torturer’s relaxed pose. Why are we looking at this image?

It’s nighttime in a bomb shelter close to the town of Khanaqin, northeast of Baghdad in Iraq. It’s the mid-1980s, during the Iran-Iraq war, and the photographer, Ali Arkady, is a child. His mother holds his legs as he falls asleep and tells him stories by candlelight; occasionally, there’s an explosion, and the neighbors and relatives in the shelter become nervous. The men peek outside the shelter, smell the air and look at the changing light. Nothing has happened, they say, and come back down. “It was a painting, a movie, and we felt almost safe down there,” Ali told me, thinking back to his childhood. “When the siren sounded, we would play a game. My father and mother would tell each child to hold on to a blanket and run this way and then the other way behind the wall to the shelter.” These are fond memories of family and closeness, shot through with adrenaline and fear.

There was no electricity at home on those nights, but the battery-operated radio would crackle on, and the presenter would describe a pause in the battle. Ali remembers his family eating and drinking together under lamplight until the early hours of the morning before the siren sounded and they would head back to the shelter. Later, covering the ISIS war as a photojournalist, Ali felt the familiar mingling of fear, camaraderie, and purpose.

In 1999, Saddam Hussein forced Ali’s family to move from Khanaqin to Darbandikhan, 100km north, because they were Kurdish. He began fixing car interiors with his family to bring in some extra money for his mother. Ali’s father wanted him to be a lawyer and have a good life after the hard years of war and sanctions, and for a while, that felt like a possibility. But life quickly unraveled under American occupation. In 2003 he returned to Khanaqin and tried to take his exams in Baquba, Diyala province. Not long after, insurgents shot Ali’s friend along with a group of police cadets in the same town, forcing Ali to give up school. Art and painting became his only comforts, and he enrolled in the Kurdish Fine Art School in Khanaqin. He thought back to the shadows and light reflecting on the walls of the bomb shelter and remembered his mother’s face as she cradled him, like something from a Rembrandt painting.

Torture was in the background of Ali’s life, used as a control and information-gathering tool under Saddam, by the Kurds, during the Iran-Iraq war, under U.S. occupation, by ISIS, and by the Iraqi army. After studying fine art, Ali devoted his life to documenting the ISIS war and explaining its effects on his countrymen and women. His photographs from this time show frontline battles and fleeing families, with flashes of intimacy and joy. Each frame tells his story over and over again; each time, the past intrudes.

The men torturing captives, raping, and killing civilians in Ali’s photographs of the battle for Mosul were meant to be the soldier-heroes of the war. But that was another, sepia-tinted version of Iraq usually seen in reports by foreign correspondents. Sometimes, those correspondents would show Iraq as a land of monsters doing terrible things to one another. I was not far away, with a different group of soldiers when Ali was taking the photographs that would force him to leave his country. I didn’t see what Ali saw. It took Ali’s experiences, his memory, and his patience to reveal the truth.

Ali’s photos never offer just one version of Iraq. Like the mind unearthing the thing we most want to forget, the unease we feel when we look at Ali’s work is precisely the reason we must look.